Note: Reposted from The Japan Times Online. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author (Jon Mitchell) and his cited sources. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of TAC Missileers Corp.

The Japan Times Online

Sunday, July 8, 2012

SUNDAY TIMEOUT

Okinawa’s first nuclear missile men break silence

By JON MITCHELL

Special to The Japan Times

In October 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union teetered on the brink of nuclear war after American spy planes discovered that the Kremlin had stationed medium-range atomic missiles on the communist island of Cuba in the Caribbean, barely over the horizon from Florida.

The weapons placed large swaths of the U.S. — including Washington, D.C. — within range of attack and sparked a two-week showdown between the superpowers that Pulitzer Prize-winning U.S. historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. called “the most dangerous moment in human history.”

Six months prior to the Cuban Missile Crisis, however, a parallel drama had played out on the other side of the world as the U.S. brought near-identical missiles to the ones the Russians stationed on Cuba to another small island — Okinawa.

While the full facts of that deployment have still not officially been disclosed, now for the first time three of the U.S. Air Force’s nuclear pioneers have broken the silence about Okinawa’s secret missiles, life within the bunkers and a military miscalculation of apocalyptic proportions — the targeting of unaligned China.

John Bordne, Larry Havemann and Bill Horn were all born during the early days of World War II, but their motivations in joining the U.S. Air Force were very different. Coming from a family steeped in military tradition, Bordne signed up out of a sense of patriotism. Havemann, a laboratory technician, saw the air force as a means to secure a stable income for his family. For Horn, the military offered an escape route from impoverished West Virginia. “Besides, I liked the color of the uniform,” he says.

Soon after joining the air force, these three men from contrasting backgrounds were assigned to the 498th Tactical Missile Group and sent to Lowry Air Force Base, Colorado. There, they first set eyes on the latest weapon in their nation’s nuclear arsenal — the TM-76 Mace. A progeny of the V-1 “doodlebug” rockets that the Nazis rained down on Britain during World War II, the 13-meter-long Mace missiles weighed 8 tons and cost $500,000 each. Packed into the missile’s guts was a 1.1-megaton nuclear warhead that, at over 75 times the ferocity of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, could obliterate everything within a 5-km radius, create a crater 20 stories deep and irradiate the landscape for decades to come.

“For such a horrendous weapon, it was very unimposing,” recalls Horn. “It reminded me of a silver hotdog with wings.”

At Lowry, the new recruits were streamed into seven-man crews and received intensive training in the missiles’ engines, guidance systems and nuclear payload. Six months later, the newly graduated “missileers” were ready for their combat postings — which they assumed would be in Europe, where the East Germans had just started work on the Berlin Wall. But to their surprise, they found themselves on a 36-hour island-hopping flight to the U.S.’s military keystone of the Pacific — Okinawa.

Although the U.S. military had seized Okinawa in the spring of 1945, months before the end of World War II, it wasn’t until China turned communist in 1949 and the Korean War broke out the following year that the U.S. became fully convinced of the island’s strategic importance. The 1952 Treaty of San Francisco, which ended the U.S.-led Allied Occupation of mainland Japan, granted America continued control of Okinawa — and it rapidly transformed it into the linchpin of its Cold War plans for Asia.

With this in mind, in 1954 the U.S. brought hydrogen-bomb armed F-100 fighter-bombers to its key hub in the Pacific, Kadena Air Base in Okinawa — the first of thousands of nuclear weapons that it would station on the island before their removal in 1972 (see accompanying stories).

When Bordne and Horn arrived in 1961 (Havemann went in 1962), Okinawa still bore the scars of World War II — civilian buildings were cobbled together from military scrap timber and the wrecks of U.S. invasion ships lay rusting off the shores. Bordne and Horn were in for another surprise. “The missile sites still hadn’t been finished,” says Horn. “Site One was a massive hole in the ground. For the first couple of months, we had to help the civilian contractors in the 100-degree heat (37 Celsius) to pull cables from the launch bays to the control centers down below.”

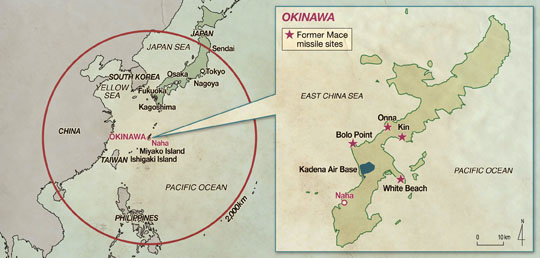

Finally, in early 1962, Bolo Point in Yomitan, the first of Okinawa’s nuclear-missile sites, became operational. Hidden beneath tarpaulins and the cover of darkness, eight Mace missiles were trucked from Kadena Air Base and loaded into launch tubes aimed over the East China Sea.

Still in the same seven-member teams from Lowry, the men began the work for which they’d been trained — “to defend the island, protect the institution of democracy and halt the spread of communism,” explains Horn with an ironic chuckle.

The men’s eight-hour shifts began with a briefing at the missile control center on Kadena Air Base to update them on the day’s weather and the current geopolitical climate. Following this, the crews drove to Bolo Point where, upon their arrival, they’d be met by an escort from the previous shift with the latest password. “It was something simple like ‘Apple’ or ‘1324’ or ‘Mary had a little lamb.’ But sometimes the escort would get distracted and forget it. That’s when they’d send in the guard dogs to see if there was a problem,” says Havemann.

Once safely past the security check, the missileers climbed into the launch site itself. Consisting of three main areas — a crew ready room, a diesel generator chamber and a launch room replete with a red telephone hotline to Kadena — roughly 10 meters away sat the eight missiles around which the men’s duties revolved. They checked the engines and fine-tuned the guidance systems, drilled themselves on safety procedures and practiced countdowns to ensure the missiles were ready to fire at a moment’s notice.

However, considering the apocalyptic power at their fingertips, life within the missile sites was terrifyingly mundane. To pass the time, the men studied correspondence classes, played endless rounds of pinochle and compared notes on the shows they’d seen recently on the bases’ nightclubs — including a (then) little-known band called The Supremes. The missileers had also been tasked by American manufacturers to field test a new gadget — microwave ovens. Bordne remembers, “They only came with one setting, so meat came out like shoe leather and the mashed potatoes had ice cubes in the middle.”

The missiles themselves created few problems for the men and the gigantic springs beneath the bunkers — designed to protect them from nuclear blasts — dampened the earthquakes and typhoons that rattled nerves among their colleagues on the surface.

But the events of October 1962 were about to dash any hopes that Okinawa would be a sun-drenched holiday posting. “At Kadena, we learned about the photographs several days before the American public. From that moment on, things became very serious,” says Horn.

The photos mentioned by Horn were those taken on Oct. 14, 1962, by an American spy plane on a surveillance flight over Western Cuba. The images revealed that, for the first time in its history, the Soviet Union had stationed nuclear weapons outside its borders. The SS-4 medium range missiles — at 22 meters nose-to-tail and carrying a megaton warhead — could reach the White House 15 minutes after launch. JFK took the news as a personal affront — branding Khrushchev “an immoral gangster,” he immediately demanded that his top brass draw up plans to bomb the Cuban sites.

Back on Okinawa, the Air Force missileers’ reactions to the photographs varied. “Some guys were mad, some sad, some were depressed and others closed and quiet,” recalls Bordne in his unpublished memoirs. “Everyone accepted the possible outcome but handled this acceptance differently.”

Over the next few days, tensions escalated in the Caribbean and the Pentagon raised the nation’s Defense Condition (DEFCON) to level two. Bordne remembers, “Our colonel told us that DEFCON 2 meant we were within 15 minutes of a declaration of nuclear war. If DEFCON 1 was reached, then we would be within five minutes of launching our missiles. A look of dread washed across everyone’s faces, and I felt the blood drain out of mine, too.”

Havemann shared Bordne’s fear. “Being trained on the nuclear weapons, I knew that the whole world was in great peril. I thought of my family in America but I could do nothing to help them. I wrote a letter to my mother knowing that if war came it would never get there. But writing it helped me mentally.”

Mingled with the missileers’ fear, though, there was also a sense of professional rivalry as the men compared their own Maces with the grainy spy-plane footage of the Soviet missiles — and concluded that the SS-4’s were technically inferior. Furthermore, they experienced a complex sense of excitement that they might finally be given a chance to put their hard months of training into practice.

According to Bordne, “After we reached DEFCON 2, another mechanic offered me $1,000 to give him my shift. That was a lot of money — a year’s salary — but I flatly turned him down. I wanted to be there for launch as badly as he did.”

For a horrifying few days, it seemed like Bordne would receive his chance as events spiraled out of JFK’s and Khrushchev’s control on the other side of the world — the Cubans shot down a U.S. spy plane and the American Navy dropped explosives on Russian submarines forcing them to surface. Hearing these developments, the Okinawa missileers steeled themselves for the announcement of DEFCON 1. Stationed at the still-incomplete Onna site, Havemann was told that if things became any worse, his crew would have to improvise by loading the warheads onto the missiles and covering the launch doors with tarpaulins.

Meanwhile at Bolo Point, Horn was locked underground for 48 hours. “A sealed canvas bag had been delivered containing our countdown instructions — and we were waiting for the red phone to ring with our launch orders from Kadena. When that time came, our officer would have broken the seal. There would have been three separate commands and then we would have launched. We were seconds away from midnight on the nuclear clock.”

But the telephone stayed silent.

On Oct. 28, Kennedy and Khrushchev finally struck a secret deal whereby the Soviets promised to withdraw their nuclear missiles from Cuba in return for U.S. promises never to invade the island and assurances it would pull its atomic rockets out of NATO-aligned Turkey.

When word reached Okinawa, Horn likened the experience to a near-missed car wreck. “At the time, you don’t realize how close things were. It’s only when you pull over to the side of the road that you really start shaking.”

But the missileers’ accounts beg the question: If that telephone had rung, where would their nuclear weapons have struck?

Until now, all three men have willingly answered every question about their time on Okinawa — right down to the “honey buckets” they used as toilets. But this issue makes them more tight-lipped. “For the purpose of your story just say that the missiles were preprogrammed and we weren’t told the destinations for security reasons,” says Bordne. Havemann’s reply: “I don’t know. And if I did — even today — I don’t think it would be wise to say.”

Horn is the only one prepared to put voice to the unspeakable. “Although we didn’t know for sure, we surmised that it was somewhere in China.”

The Maces’ relatively short range of 2,000 km put almost the entire Soviet Union, with the possible exception of Vladivostok, tantalizingly out of the missiles’ reach — and this technical data, combined with Horn’s suspicion, illustrates one of the biggest failings of 20th century U.S. military intelligence. Today the 1959 Sino-Soviet split is well-documented — Khrushchev and Mao had come to blows over Russia’s refusal to help China develop nuclear missiles combined with a fratricidal ideological debate over communism’s future. However at the time, the Pentagon had blindly assumed that the two countries were allies. This misconception laid the basis of America’s infamous blueprint for atomic war — the Single Integrated Operational Plan — dubbed by one government adviser as a “massive, total, comprehensive, obliterating strategic attack on everything Red.” While JFK had made token changes to the plan in early 1962, the amendments apparently hadn’t filtered down to the missile control center on Kadena.

Given the tensions between China and the Soviet Union, it is highly likely that Mao would have sat out the Euro-American armageddon sparked by the Cuban Crisis. But had the Okinawan Maces annihilated Shanghai and Beijing, killing untold millions of neutral Chinese civilians, Mao would undoubtedly have lashed out.

While the three missileers are understandably reluctant to discuss the targeting of China, they all agree that the U.S. missiles on Okinawa made the island a target. Bordne worried about the possible “evaporation of Okinawa in a preemptive or retaliatory strike,” while Horn believes that “The Okinawans were a human shield.”

Havemann raises an even more frightening prospect for the islanders still traumatized by the Battle of Okinawa in which a third of the civilian population had died — a land invasion by Russian or Chinese troops. At the same time he was warned he may need to load the warheads into the Onna Maces, Havemann says, “We were told to get our equipment, helmets and backpacks ready in case we had to head for the jungles. If we were overrun by an attacking force we were to destroy the nuclear weapons, seal the sites and do what we could to survive.”

Okinawa and atom bombs: A Timeline

1945 U.S. military seizes control of Okinawa after three months fighting.

1952 Treaty of San Francisco ends U.S.-led postwar Allied Occupation of mainland Japan, but grants the U.S. military jurisdiction over Okinawa.

1954 The crew of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon #5 are irradiated when the United States underestimates the strength of an H-bomb test in the Pacific. More than 30 million Japanese people sign a petition in protest. For the first time, the U.S. military secretly stations nuclear weapons on Okinawa.

1956 The Ryukyu Assembly of Elected Officials demands the withdrawal of all nuclear weapons from Okinawa and any other islands.

1962 The first of four Mace nuclear-missile sites becomes operational at Bolo Point, Okinawa.

1965 The U.S. loses a hydrogen bomb from the U.S.S. Ticonderoga 130 km off Okinawa’s coast.

1966 Iejima Island residents successfully block the deployment of U.S. Nike nuclear missiles.

1967 Prime Minister Eisaku Sato first suggests Japan’s three non-nuclear principles: Not to possess, manufacturer or allow the introduction of atomic weapons.

1968 A U.S. B-52 strategic bomber crashes near nuclear-warhead bunkers on Kadena Air Base.

1969 Japan and the U.S. conclude a secret agreement — allegedly still in operation — which allows the U.S. to reintroduce nuclear weapons to Japan during times of crisis.

1971 Washington demands Tokyo help to pay for the removal of nuclear arms from Okinawa — the first official U.S. admission of the presence of nuclear weapons on the island.

1972 Okinawa reverts to Japanese control.

Ironically, in his Oct. 22 televised speech in which he broke the news about the Soviet missiles in the Caribbean, JFK accused Castro of turning Cuba “into the first Latin American country to become a target for nuclear war.” Now it seems clear that not only the 7 million Cubans but also the 900,000 residents of Okinawa were pawns in a far larger play among distant superpowers who apparently cared little about the civilians whose lives their nuclear weapons were supposed to protect.

Fifty years after their days on Okinawa, all three American missileers are now retired with time to reflect upon their roles in human history’s most dangerous moment.

Of the three, Horn is the most rueful. “We were all just kids doing a man’s job. The American military machine taught us that it was our right to take anything or go anywhere we wanted. But we never realized that people didn’t want us or our weapons on their island.”

Bordne is prouder that he could perpetuate his family’s long military heritage. But the ensuing half century has revealed to him some unexpected similarities with his erstwhile enemies on Cuba. “I used to hate the Russian missileers, but after reading accounts of their experiences, it is clear that they exercised the same restraint and clear judgment as we did. Now, I know that none of us wanted to alter life on this planet for eternity.”

Havemann shares Bordne’s sense of responsibility and he is a firm believer in passing on the lessons of 1962 to future generations. “Nowadays, when I watch the news, it seems some people, like the leaders of Iran, think that a nuclear weapon is little more than a big stick of dynamite — and it’s fine to set one off here and there. It gives me a strange feeling in my stomach and sometimes I come close to tears.”

Jon Mitchell is a Welsh-born writer based in Yokohama. In 2011, his research into the U.S. military’s usage of Agent Orange on Okinawa during the Vietnam War prompted the Japanese government to announce that it would seek disclosure from Washington on the issue and this research was the subject of two TV documentaries in May 2012.

The original article can be found here. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/fl20120708x1.html

A related article Okinawa, nuclear weapons and ‘Japan’s special psychological problem’ can be found here. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/fl20120708x3.html

I was with the 498th MMS from 9/1961 – 3/1963 at Kadena. We unloaded the TM-76B missiles from cargo planes, loaded them onto flat bed trailers, took them to the maintenance area assembled, fueled, tested the J33 engine, delivered them to each site.

I came close to re-enlisting but with rank being somewhat frozen … back to college I went.

I was stationed at the Nike Missile site at Yonabaru, Okinawa from 1959 to 1960 and we had nuclear warheads. And, we weren’t the only Nike site on the island so it seems logical that the others did also.

Like Joe Lindsay I was factory trained but unlike Joe I volunteered for duty on FTD911L. After setting up the school at Lowery I left for Kadena for 36 months as guidance system specialist on the training detachment. I moved to Orlando AFB as a launch crew trainer for my last 2 years when we dismantled the training center.

The Cuban crisis and JFK assassination did create some tense moments over there. Many memories and stories have come out of those 8 years. It’s great hearing from you all.

Robert Cornell ( Bob ) as I recall,

Yes we did eat many a pizza, plus Heinekin beers. I do apologize for not responding sooner, just now saw the post from February 2014. Much has happened since then and also 2010. Please contact me at above address.

Just this morning I received a call from a very good friend from Air Force days, particularly Kadena. Not sure what Crew he was on , Gene Stirewalt , from Charlotte NC. Mech #5 was on a Standardization Crew responsible for testing to determine if we were ready. He was also my BestMan at wedding in 1963, exactly 20 days before JFK assination. I was stationed at Lockeborne AFB in Columbus , Ohio, he was freezing at Selfridge AFB , Michigan.

I have a boatload of pictures of you and all the guys on rooftop of our barracks from 1961, would love to send them your way.

Bill Horn

I enjoyed reading this. I started on the TM61C, then was trained on the TM76A after the Air Force decided I should stay at Lowry AFB as an instructor. I went to the TM 76B training at the Martin Company. At Lowry, we wrote the training material and started teaching. When I finally went on the first of two tours on Okinawa, it was as a Crew Chief on crew 7. I spent 12 years in and was in SAC as an Avionics tech on B52s and KC135S. I took the PME test and worked in PME labs at Altus AFB and Webb AFB. As I have noticed, we are proud of our service. I enjoyed reading your posts and assume that I may have trained some and some may have been trained at Lowry by me.

I was stationed at Bitburg AFB, Germany, Idenheim site on the Mace B missile. I was there when the 7 day war transpired in 1968. We went on total alert until it was over. I can relate somewhat how the crew members acted during the Cuban Missile crisis. Missile duty was not bad but we spent 12 hour shifts in Germany at the sites and we had only a total of 16 birds. The training was moved from Orlando AFB to Lowry AFB, Denver in 1966 and we were part of the first crews that went thru training there and our assignment was Denver, the next set of crews went to Kadena. One of the Mech 5 trainers told a story that the missiles at bays 21 and 22 at the Caper we loaded with nukes during the Cuban crisis. We served our time with pride and were proud of wearing our missile badges at Bitburg because we knew the pilots and maintenance crews on base didn’t have those badges.

I was a member of the first operational crews with the Mace B, crew #5 with Capt. Robt. Klintworth. The story is basically factual (ie training and honey buckets, microwave and boredom). The island was beautiful and we enjoyed our tour other than the early pulling cables. I was a 31157, guidence control systems mech at the time. I recall a Bill Horn and believe we spent time togeather at A1 pizza in downtown Koza city. Would like to hear from you, Bill

Yes, It was Fred and I who , put together, from the very beginning, all rocket assist, warheads, wing destructs, and cable releases. There was only 2 of us and we worked 7 days a week and 12 hour shifts to get them together, transport them, just to mention that we drove the trucks, and installed all this in the sites. What memories those were. Proud to serve our country.

corrected web site address

I was with the 498mms from 9/61 thru 12/62. Weapons mechanic on the big boomers. Edgar C. Brown (Carl) was the other weapons mechanic. The two of us were kept pretty busy. The Special Weapons Officer (major) kept us in line and was a fine officer. Can’t remember his name. Carl and I got together a couple of years ago for the first time in 50 years. Wonderful reunion. Lots of stories from Okinawa that can’t be told here. God bless those who serve and served “ALL GAVE SOME AND SOME GAVE ALL”

I was in the 498th MMS from early 1962 thru mid 1963 as a Guidance Systems Tech. in the Kadena maintenance compound. We were frequently dispatched to the operational sites to try and correct guidance system problems without having to have the bird pulled and returned to the maint. facility. It was always interesting going out to the sites which were in combat ready status. The Launch crews took their mission very seriously. It always made me proud to fix a problem onsite and keep the bird operational.

During the Cuban crisis we were issued .45 cal. pistols and holsters and required to carry at the maintenance yard———however we WERE NOT issued any ammo or clip magazines! This lack of ammo was very visible when our weapons were holstered; however the civilian Okinawan guards assigned to the maintenance yard were, as always, fully armed with live weapons!

We were all quite relieved when the crisis was over. It certainly was I time I will never forget and the experience gained interacting with my fellow airmen in time of great danger has been a valuable asset to me in my civilian life.

I was in the 498thMMS in 1962-63 working on the guidance system in the maintenace yard on Kadena.

Security was extremely tight during our infrequent visits to the hardened sites. We laughed and passed around the ‘urban legend’ of MPs running for their lives when one of the missle transporter’s brakes caught fire while on the way to the maintenance yard.

JFK’s assination put us on high alert. As I was a ‘short-timer’ in late Nov., I was concerned about being frozen in place and not returning to ‘the land of the big BX’.

Great memories some fifty years on.

I’d love to hear from any 498MMS vets out there.

I spent many years testing’s for Radiation back then we had no test Monitors.

However the Va denied my claims. also PTSD. All done in the MPS VA System.

Now that I am in ND. Fargo may Be Different. Kadena Air Base, And our old Launch sites. Are as you Know, are all gone but one. And so, Bless you all for what you have done for God and Country, I wish today with all the world Problems. That our Current Goverment. Stay’s On track and Funds our great Armed Forces.

I thank you for all your dedication to your duty and country, you all had the highest of responsibility that any airmen could pocess. I was stationed on Okinawa for 13years on 3 tours as a pararescueman, My first tour was Dec 72, second 76 third 81, all tours were wonderful but demanding and extrembly busy. I completed 26yrs with 3 tours in Vietnam and tours all over the world and never regreted my service for a moment. You all hang in there and maybe you all can publish a book. God bless. Duty, honor country always.

I was 20 years old, when I was sent to Okinawa, 498 Tac Missile Gp. Never realized the extent of the Cuban Missile Crisis. I still belong to the 498th I am now 72 however a friend who lived in Koza City Next door Was In the 1st Special Forces and served 3 Tour’s In Vietnam What great Memories.

Take Care and God Bless, all who have Dedicated there Lives for our Great Country.

The Cuban missile crisis was the scariest few days I’ve lived through in my 65 years.But I found out in the mid 1980’s things were worse than we knew.I always assumed it would have been us vs the Soviets.

I was dating this young lady who was born on Okinawa in 1962.Her father was a retired Col. who had been a fighter pilot in WWII and 2 decades later at 46

was one of the oldest fighter pilots in Vietnam.After a couple martinis he told me this story.At the end of WWII he landed the 1st plane in Shanghai, China and spent about a year there.In ’62 he was flying nuclear bombs in Okinawa.He said the scariest days he spent during his 32 years of service were when they scrambled during the Cuban missile crisis.His target was a church in Shanghai.

Thanks for the great Post, I was one of the 498th Tac Mis. Personnel. I drove Top SecretTest Monitors to all the Launch Sites on Okinawa.

I was stationed at the Nike base IFC (Integrated Fire Control) site on Naha AFB, nearby the above Mace missiles. I did not even realize that the Nike Hercules missiles had nuclear warheads until recently doing some historical research on a former Nike base in Mahwah NJ I spoke to a former ordnance tech about a 1958 incident where a Nike Herc was ignited in error on the AFB. He advised that it had a nuclear warhead. He said that he had passed behind that missile a couple of minutes before it inadvertantely took off. I was stationed there around 1963 but had heard about that incident.

The other unusual situation was that there was a nuclear sub expected to dock at Naha. And it was expected that the Okinawans who were expected to demonstrate

and possibly riot. So we were trained in riot control, to be called out in case there were a riot. We were advised to take our rifles with no bayonet or ammunition. We would be supported by sharpshooters in case there use was necessary. I thought it ironic that they would be demonstrating against a nuclear sub when there were already so many Nike Herc nuclear warheads already on the island. I guess that they did not know that the Nikes or bombers on the Air Force bases, and Mace missiles also carried nuclear weapons alreaady there.

Since there was a class-action lawsuit attempted a number of years ago by Nike and Hawk radar techs for cancer caused by the radars, I had put myself on the Veterans Administration Health Care ionizing radiation registry. I also put myself on the Agent Orange registry because I understood that a claim from a veteran who had been stationed on Okinawa had his claim for exposure on Okinawa approved. This was in spite of the fact that the Defense Department said it had no record of AO ever being on the island. It was also believed that the AO was used as a herbiside at the various bases on the island. Our Nike base IFC was on the perimeter of Naha AFB, so must have been an area that was sprayed. Fortunately, I do not yet have any type of cancer that I know of, as many of the veterans have had. My son is in special education, and I always wonder if AO caused this.

It has now been approx. 3 weeks since the above poster , the outspoken Mr. Osborn, made his comment about the “dipshits” from Kadena. I will wait a total of 30 days before responding as one of those “dipshits”. Other folks might like to do more than lurk in the shodows of their computers.

As a 61-C, 76-A, 76-B, MM II, and MM III grunt (among other jobs in a 22+ year career), I am forced to believe that those three guys were either badly misquoted or are complete dipshits. In either case, they are naive beyond belief.

Stationed at Homestead AFB We were already going thru prep before Pres Kennedy made his TV speech . Trainloads of Army personel. over 200 planes with some having pilots sitting in the cockpit. Witnessed in bld 360 the base being overturned over to TAC from SAC.